It’s no secret: animals have sex, just like we do.

Biologically, sexual reproduction is defined as a process by which two organisms of differing sexes combine genetic information to create new offspring. This shuffling of genetic information fosters genetic diversity, which allows species to better adapt to their changing environmental circumstances. If a gene is beneficial in an organism’s survival, then that organism is more likely to survive, reproduce and pass on the gene: the faster antelope is more likely to outrun the lion. The opposite is true for disadvantageous genes: the slowest antelope is more likely to be eaten by the lion.

But, in cetaceans, the story of sex doesn’t end with that stale, biological definition. In fact, that’s just the beginning.

Like humans, cetaceans not only have sex, but they experience sexual pleasure. A 2022 study published in Current Biology suggests that female bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) possess anatomically functional clitorises that are important for mating and play behaviors. Female bottlenoses often stimulate each other’s clitorises in sexual interactions, and the position of the clitoris indicates that it is likely stimulated during male-female reproduction.

Unlike dolphins, no clitoris-type physiological structure has been found in humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae). Instead, female humpbacks have a genital slit accompanied by two mammary slits on either side, which are used for nursing calves. However, female humpbacks’ lack of clitoris does not equate to a lack of pleasure: a 2022 study published in Aquatic Mammals suggests that female humpbacks may purposely position their mammary glands and genital slit above bubbles blown by male humpbacks. This finding indicates that females may experience pleasure from bubble stimulation.

Bubble behaviors have been documented in most types of whales and provide a variety of different functions; bubbles are formed during stressful situations, in aggressive male-male competition, in play, in aversion tactics, and in foraging situations. However, bubbles used for sexual pleasure are a novel concept.

Primary investigator Meagan Jones and her co-authors at the Whale Trust documented this behavior during the breeding season between 2000 and 2003 in Au’au Channel in West Maui, Hawaii. Over the course of a fourteen-minute video, three males were observed producing bubbles directly under a female’s genitalia twelve separate times. Instead of fleeing, the female seems to accept these bubbles, exhibiting behaviors such as “rolling toward, arching, or slightly lifting and/or moving her tail above the bubble releases”.

Jones et al. propose two possible explanations for these novel behaviors. On one hand, the authors hypothesize that these bubbles could serve a pre-sexual purpose – in other words, foreplay. Alternatively, the authors propose that the observed female could have been in late pregnancy and the bubbles could stimulate the release of oxytocin, a hormone essential for giving birth. It is also interesting to note that in humans, oxytocin is also released during orgasms. At the end of the paper, Jones mentions potential research into the hormonal state of the female whale receiving this behavior. Understanding the female’s reproductive state (ie if she was in late pregnancy) would elucidate the context of the behavior.

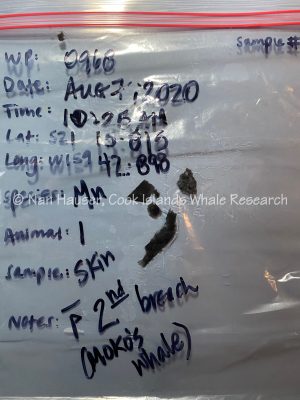

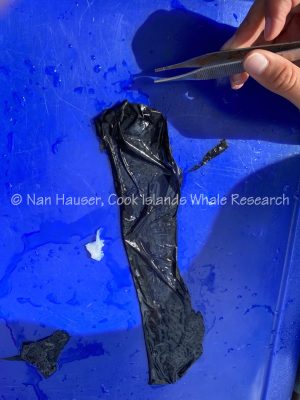

Prior to this publication, no research has been published on the use of bubbles in male-female sexual interactions in humpback whales. However, this season at Cook Islands Whale Research, we have observed this behavior in humpbacks in the waters around Rarotonga and have captured it on camera: Following a group of one female and two male escorts for over two hours, we observed the primary male escort blowing bubbles under the genital slit of the female multiple times. She spent a large amount of surface time in a side-on position, seeming to receive the attentive behaviors of the males, which included bubble streams and bursts.

Though we clearly cannot yet draw conclusions from our observations without further data collection and analysis of these behaviors, Jones et al.’s profiling of this behavior provides an exciting new framework with which to analyze our data and potentially build on her hypotheses.

This line of research provides another interesting parallel between human and whale behaviors, demonstrating again why we connect with them so deeply and why they deserve our respect and protection.

Picture of male humpback (center frame) blowing bubbles under female (top left)

References:

1 Brennan, P. L. R., Cowart, J.R., & Orbach, D. N. (2022). Evidence of a functional clitoris in dolphins. Current Biology, 32(1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cob.2021.11.020

2 Bagemihl, B. (1999). Biological Exuberance: Animal Homosexuality and Natural Diversity (Macmillan).

3 Jones, M. E., Nicklin, C. P., & Darling, J. D. (2022). Female humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) positions genital-mammary area to intercept bubbles emitted by males on the Hawaiian breeding grounds. Aquatic Mammals, 48(6), 617-620. https://doi.org/10.1578/am.48.6.2022.617

4 Moreno, K. R., & Macgregor, R. P. (2019). Bubble trails, bursts, rings, and more: A review of multiple bubble types produced by Cetaceans. Animal Behavior and Cognition, 6(2), 105-126 https://doi.org/abc.06.02.03.2019